Allen M. Junek

Sermon for the First Sunday after Pentecost, Trinity Sunday, Year B 0 5/30/21

Isaiah 6: 1 – 8

Canticle 13

Romans 8: 12 – 17

John 3: 1 – 17

In the Name of the holy and undivided + Trinity: one God,

in whom is heaven. Amen.

It was a warm summer evening in New York City. The year was 1969, and the United States–and indeed the world–was emerging from one of its most politically charged and tumultuous decades.

None of that mattered, though, because it was a Friday night. There were drinks to be had, bars to patron, and strangers to kiss. One such bar was named the Stonewall Inn and it had built for itself a reputation for being one of the few havens, a refuge, for the city’s LGBTQ+ population.

One reason for the Inn’s popularity was that few bars in New York, even gay bars, permitted members of the same-sex to dance with one another.[1] The front room of the Inn, facing Christopher Street, was dominated by a large dance floor. Men danced with men, women with women, and people whose gender was indiscernible or obsolete did the same, often for the first time in their lives. A well-stocked jukebox in the corner ensured that these bodies would be twisting and turning, shimmying and jiving, out on this dancefloor well into the morning hours.

That is, if the cops hadn’t shown up.

Perhaps some of us here remember that night, and the days, weeks, and months to follow. I doubt that Miss Marsha P. Johnson (of blessed memory) ever imagined what would come of that first brick, or that that night’s riot against police brutality would effectively kick off the gay liberation movement. I also doubt she ever imagined that 52 years later—nearly 6 years after the legalization of same-gender marriage–a group of Anglicans, of U.S. Episcopalians, would be remembering her name during mass on Trinity Sunday.

Now, you may be wondering what on earth does an old pub in Greenwich Village have to do with the Triune God? Well, perhaps more than you’d think.

For the past couple millennia, countless people have tried to understand what Christians mean when we speak of the Triune God. Throughout Christian history people have attempted to nail down the doctrine surrounding the Trinity into declarative statements. St. Patrick, for example, famously tried to explain the Trinity to the Irish using a clover leaf, or so the legend goes.

I wish the legend also said that this was a pretty poor analogy, just like every other analogy we have used to make sense of the Trinity. Poor analogies are probably part and parcel to why the average person thinks God is an old white man in the clouds whose dying son left his ghost behind to haunt us.

Even today, preachers the world over will try to explain the Trinity–and they will fail, precisely because the Trinity is quite unlike anything else we have ever seen or known. If you ask me—which you didn’t, but I’ll tell you anyway—the Trinity is one of the most beautiful aspects of our faith that we can’t see and we can’t know. At least not really.

Among the many declarative statements about the Trinity, perhaps the most famous are those found in the creed of St. Athanasius. In one section this creed asserts, God is the “Father incomprehensible, Son incomprehensible, and Holy Ghost incomprehensible.” This might very well cause many of us to mutter, “Well, preacher, this whole thing is incomprehensible.”

And you know, that’s not a bad place to start!

As Anglican Christians we are comfortable with the incomprehensible–or at least we ought to be, considering one of our great gifts is the ability to chart a middle way. Having mystery and paradox–rather than certainty–at the heart of our faith shouldn’t bother us too much. I mean, my goodness, have you considered some of the other things we believe? In a few moments, bread is about to become Flesh and Blood.

Take for example, the Ark of the Covenant—you know, that gold box from Indiana Jones? It’s also the vessel that housed the tablets of stone Moses brought down from the mountain, and it was the place where the Presence of God dwelt in a special way. If you recall, just moments ago we spoke of this box in Canticle 13: “Glory to you, seated between the Cherubim.” You see, on the lid of this box were the figures of two angels, kneeling towards the center. But in the center, instead of an image of the Deity, what was there?

Nothing. Nothing at all.

It was understood by our ancestors, the Hebrews (or at least some of them) that the God who brought them out of Egypt is beyond all comprehension. The prophet Isaiah, as we can see from today’s first lesson, figured this out firsthand. When ushered into the Presence of God, what did he do—what could he do—but fall on his face and say, “Woe is me!” Who am I, that I should see God?

I think this was also understood by our more recent Christian ancestors, especially the ones who had a hand in shaping the calendar of our Church Year.

At the beginning of the year, in Advent and Christmastide, we celebrate the incarnation of this unknowable God among us. The Word became flesh, and we have seen his glory, the glory of a father’s only son (Jn. 1:14). Isaiah, at long last, is not the only one to fall down in worship.

Then we entered the Epiphany season, when it was revealed that God’s promise to save was much more broad in scope than previously imagined. It includes Gentiles, non-Jews, which I imagine is very Good News for most of us in this room! Emerging from Epiphany we entered the holy season of Lent, where we considered the cost of our salvation and the ways we continue to separate ourselves from God’s divine life.

Next, the Easter season, rejoicing in the day that changed everything. Then Ascension, where our human nature, united with Christ in his divinity, was raised to God’s right hand, such that what we are might ever be where he is. And then last week, Pentecost: the day when God came with fire. When the Spirit was poured out upon the Twelve, upon Blessed Mary the God-bearer, and the countless unnamed women apostles who were gathered there with them.

Between Advent and Pentecost, the coming of Christ and the descent of the Spirit, it would seem as if we have this whole religion thing figured out. If the year ended at Pentecost, I doubt there would be much more to say.

And yet, here comes Trinity Sunday just on the cusp of Pentecost as if to say, “Wait! Pump the brakes! God is One, but we just experienced a God who is also Three? How the heck is that supposed to work?”

You see, the doctrine of the Trinity did not come from the top down. It did not emanate from Rome, or from popes, or kings. Certainly it was corroborated by bishops and ratified in councils, but historically speaking, it emerged relatively quickly as an attempt for Christians to make sense and speak about the experiences they were having in their communities through their common worship, common lives, and dare I say, common prayer.

They knew how to count. They also knew their experiences of a God who is One yet Three were paradoxical. The Church Calendar teaches us, and the placement of today’s feast is instructive insofar as it reorients us toward not only the Mystery-Who-is-God, but the melody that exists at the heart of the Mystery.

I suppose that if one’s looking for a faith that has all the answers, we shouldn’t recommend ours. Nicodemus, in today’s gospel, came searching for answers. “How can these things be?” he asked Jesus. To be fair, Nicodemus probably didn’t find Jesus’ response all that helpful, but something about Jesus’ curious answer must have stuck, because Nicodemus would be among the few that prepared our Lord’s Body for burial. I like to think Jesus knew what Nicodemus would do for him, and that our Lord understood that mystery is often of far more value than certainty. We here under the patronage of St. Thomas the Apostle know intimately well that the opposite of certainty is not doubt, but faith.

So, today especially, I’m thankful that the burden is not upon me, you, or anyone for that matter, to explain this Mystery. The Godhead is not waiting for us to give reasons for his, her, their, even it’s Being. In conversations about the Trinity, theology often devolves into an argument about what’s up God’s skirt, or a justification for tarring and feathering anyone who thinks differently than we do–such that we are prone to lose sight of this doctrine’s invitation.

And that is an invitation to just shut our mouths.

The goal of theology is not to publish the next volume. Preachers don’t preach in order to hear their own voices (or at least most of us don’t). No—the aim of all our words about God, the purpose of all the books that have been written, is to get us to the brink of that encounter in which we realize words no longer matter.

It’s an invitation to stop our squabbling, feel the rhythm, hear the music, and to step out on the dance floor.

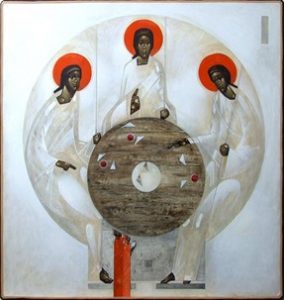

Christians who came long before us used the word perichoresis to talk about the Trinity, it’s a mouthful, but what I find most interesting is that our word “choreography” comes from the same place. The choreography of the Triune God is a fluid union of dancers such that we cannot tell the dancers apart from the dance itself. It’s this sort of mutuality of giving and receiving and self-offering that the image on the front cover of your service leaflet tries to capture (…it also would appear as if every hour with God is happy hour…)

Now, if you would, take a look at the image on the next page. I chose this image deliberately. Although there are three figures around the table, there is yet room. Another can join. This icon makes explicit what many are given to miss, and it is that we should pull up a chair and participate in God’s divine life. If the Trinity is like a dance, then we are meant to join the choreography.

Scott Erickson, “Trinity (c) 2021 Scott Erickson Art Shop

Scott Erickson, “Trinity (c) 2021 Scott Erickson Art Shop

What then, is this gathered community, if not our dance partners, and what is this altar if not the place where we may best learn the steps?

And you know, that’s the ding-dang Gospel–that God…desires…us. God desires us!

“For God so loved the world that They sent the Son–God from God, Light from Light, true Chord from true Chord–so that everyone who hears the music may not be out of step, but will be caught up into the dance of God’s abundant, unending life.” (Jn. 3:16, from the ARV Bible: Allen’s Revised Version).

So whether we realize it or not, this God of the Dance invites us to learn the steps. The one who sung worlds into being, embracing them in a sacred dance, beckons us to arrange our lives in rhythm with Their music. The music is playing all around us, whether we choose to hear it or not.

Is not this altar also the place where we tune our hearts to hear the music?

Those folks in Greenwich Village that night in 1969 heard the music; and so, forfeiting their shame and their fear of being caught with two left feet, they danced. They knew that at any moment, the overhead lights could be flipped on and they could be beaten, arrested, both, or worse. Indeed, many of them were. But now our children’s children will dance to the beat of the drum that rattled the walls of the Stonewall Inn early that Saturday morning. It was this same beat that first set fire to the Sun, the rhythm which caused our hominid ancestors to first look up at the night sky, and the tune that continues even here and even now.

I’m sure we’re all familiar with the slogan that was so often repeated by LGBTQ+ folks and their allies in the campaign to fight for marriage equality: “Love Wins.” It’s more than a pithy statement, however. The argument that love wins is an ancient theological claim in our tradition. In our own tumultuous times, it is the firm conviction that love indeed wins that offers us hope in this present moment of Pride even though 2021 has gone on record as being the worst year in recent history for state legislative attacks against the LGBTQ+ community. The same Spirit that grabbed hold of Marsha P. Johnson is the same Spirit that hovered over the water of our baptism; and so like her we are compelled to protest cruel and unjust systems of policing—precisely because of our belief that love wins. For if love wins, then a day is coming when our current methods of policing and punishment will one day be obsolete—because Love will have won.

If “Love Wins” then the love that is demanded of us is a love that is sacrificial and self-offering. Only then may we set about the work that is necessary for ushering in a new heavens and new earth in which the love we give cannot be distinguished from the love we receive, and the love received is none other than that old ballad that forms the heart of reality itself.

And so, may the Loving One, who sung the world into being, tune our ears to hear their song. May the Liberating One, who danced among us at the wedding in Cana where he turned water into wine, let us drink deeply of the mysteries of our faith. And may the Life-Giving One, who is poured out upon all flesh and danced in tongues of fire, teach us the steps to this great dance of endless, deathless Love.

Happy Pride, amen.

[1]Bausum, Ann. Stonewall: Breaking Out in the Fight for Gay Rights.